Two things happened almost simultaneously and they intertwined. One involved the

Curator of the Mathematics Collection of the Science Museum in London; the other

involved Sir Roger Penrose. Everyone has heard of the Science Museum but, unless

you have an interest in science or maths, you may not have heard of Sir Roger Penrose.

Many would argue that he is the greatest living British mathematician. He is very

highly-

Much of Sir Roger’s work was involved with discovering shapes that fit together.

Whereas we played with anything that took our fancy, he worked very seriously within

strict self-

After hearing that we were working with shapes whose angles had to be a multiple of 45 degrees, he sent us a sheet of paper which was completely covered in squares and 45 degree rhombuses in a random manner. There was no repeat to the tiling as it moved across the page. He had annotated the drawing and outlined a small area in blue and, around that a larger green area, to show what he had discovered. It was complicated stuff. The part that was easiest to grasp was that this was an aperiodic tiling. You can look this up in books where you will find detailed ways to annotate and define the properties of shapes.

We were back in the realms of dealing with intellectual, academic mathematicians who knew far more than we did. This was a little daunting but our incomplete understanding didn’t deter us. We studied the subject long enough to understand a little more then returned to the tiling. Steve wanted to colour it but before he could do that he had to redraw it on the computer, which was quite a tedious task as there were hundreds of tiles.

There is something known as the Four-

We had a dilemma about how to use it. We couldn’t use it all. There was far too much and knitted pieces would have been tediously small to make. Also, it wouldn’t have a straight edge as the pieces poked out at the sides, so it would be difficult to hang.

Eventually we decided to take a section which made a unit in itself. In a way this

was a disservice to the original but we do include a copy of the complete coloured-

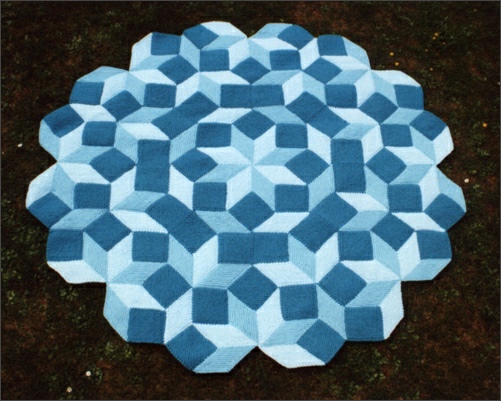

The area we took is circular, with an uneven edge where the shapes stick out. It has 160 pieces which make up eight sections. In these eight sections there are four of one arrangement and four of another. They fit together to make a design that repeats four times around the circle.

It is circular and looks a bit like a flower. There was only one choice for its name. It had to be Penrose.

At around the same time the Curator from the Science Museum got in touch, by email. She had heard of our work and wanted to buy Square Deal for the museum. Despite our resolution never to sell it would have been rather churlish to turn down such a request. It was time to make an exception. You may remember, from the Square Deal story, that it was stapled to a board and hung in my classroom. Because it was small it had stayed there ever since, gathering dust. I offered to make a new version for the museum but they insisted that they wanted the original, and that they would also like to buy Counting Pane and Pythagoras Tree.

Square Deal was unpicked from its board. The dust was vacuumed out of it and it was unceremoniously stuffed into a bag, along with the other two pieces, and I set off to deliver them.

Several of the London museums share a vast store, away from the museums themselves. This was where I had to go. I knew I had to take all the right documentation to get past the security guards outside but, until I got there, I hadn’t thought about what this building might contain and how intense the security had to be. There are millions of pounds worth of treasures stashed away in that store. Once inside I had to wait to be collected by the Curator I had been communicating with and, when she arrived, she led me into the depths of the building, passing alternately through huge security doors and fire doors. Apart from the level of security it was no different from many other buildings. There was nothing to see as every door we passed was firmly closed.

I was led to the Conservation Department and my Sainsbury’s carrier bags were taken from me with the utmost reverence. The staff were taking far more care of my work than I ever did. They may have cost me very little to make but to a museum every artefact is respected in the same way. Monetary value is of no importance. My hangings could have been made from gold and they would not have been better treated. I was told that they would be treated in some way to preserve them and then stored in tubes until needed.

In the course of conversation, by chance, I told the Curator about Penrose. By a

strange coincidence she was planning a Penrose exhibition and asked if the museum

could also buy Penrose. I was happy to agree but asked her to wait a while as I was

in the process of making a second version. The first had been in Steve’s choice of

colours – red, orange and yellow. It was very striking and very effective. The colouring

of the pieces had the effect of forming cubes that had disappeared or moved somewhere

else when you looked at it again. I don’t like making the same thing twice but this

was an exception as it was quite clear that a more subtle choice of colours would

have very different effects. The second version was in three shades of pale blue-

This is one of the few afghans that Steve and I have not agreed about. He preferred his, I preferred mine. We offered the museum a choice. They chose the red version and Steve still delights in mentioning this at every opportunity. For complicated legal reasons, the Penrose exhibition did not take place.

At the time we delivered Penrose, the Curator asked if I could knit a Peano curve. I had to admit that I hadn’t ever heard of such a thing. She did not know anything about the curve herself, except that she had seen a picture in a book. A few days later she sent some pages photocopied from a mathematical tome and we quickly decided we could not knit this as it just didn’t fit with the way we did things. It could not be made from our shapes as it was fundamentally a squiggly line crossing a grid. We kept the papers and carried on with other things.